JUnit 4 vs. TestNG

From NeoWiki

m (→Skipping, not failing) |

m (→Skipping, not failing) |

||

| Line 142: | Line 142: | ||

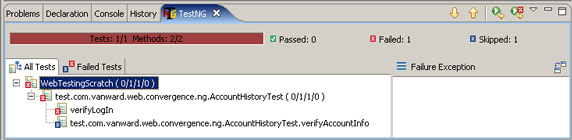

If you ran this test through TestNG's Eclipse plug-in (for example) and the verifyLogIn test failed, TestNG would simply skip the verifyAccountInfo test, as shown in Figure 1: | If you ran this test through TestNG's Eclipse plug-in (for example) and the verifyLogIn test failed, TestNG would simply skip the verifyAccountInfo test, as shown in Figure 1: | ||

| − | Figure 1. Skipped tests in TestNG | + | Figure 1. Skipped tests in TestNG<br /> |

[[Image:Skipped_Tests_Eclipse.jpg]] | [[Image:Skipped_Tests_Eclipse.jpg]] | ||

Revision as of 07:45, 3 March 2007

- Why TestNG is still the better framework for large-scale testing

Andrew Glover, President, Stelligent Incorporated

29 Aug 2006

- With its new, annotations-based framework, JUnit 4 has embraced some of the best features of TestNG, but does that mean it's rendered TestNG obsolete? Andrew Glover considers what's unique about each framework and reveals three high-level testing features you'll still find only in TestNG.

JUnit 4.0 was released early this year, following a long hiatus from active development. Some of the most interesting changes to the JUnit framework -- especially for readers of this column -- are enabled by the clever use of annotations. In addition to a radically updated look and feel, the new framework features dramatically relaxed structural rules for test case authoring. The previously rigid fixture model has also been relaxed in favor of a more configurable approach. As a result, JUnit no longer requires that you define a test as a method whose name starts with test, and you can now run fixtures just once as opposed to for each test.

These changes are most welcome, but JUnit 4 isn't the first Java™ test framework to offer a flexible model based on annotations. TestNG established itself as an annotations-based framework long before the modifications to JUnit were in progress.

In fact, TestNG pioneered testing with annotations in Java programming, which made it a formidable alternative to JUnit. Since the release of JUnit 4, however, many developers are asking if there's still any difference between the two frameworks. In this month's column, I'll discuss some of the features that set TestNG apart from JUnit 4 and suggest the ways in which the two frameworks continue to be more complementary than competitive.

| Tip: Running JUnit 4 tests in Ant has turned out to be more of a challenge than anticipated. In fact, some teams have found that the only solution is to upgrade to Ant 1.7. |

Contents |

Similar on the surface

JUnit 4 and TestNG have some important attributes in common. Both frameworks facilitate testing by making it amazingly simple (and fun), and they both have vibrant communities that support active development while generating copious documentation.

Where the frameworks differ is in their core design. JUnit has always been a unit-testing framework, meaning that it was built to facilitate testing single objects, and it does so quite effectively. TestNG, on the other hand, was built to address testing at higher levels, and consequently, has some features not available in JUnit.

A simple test case

At first glance, tests implemented in JUnit 4 and TestNG look remarkably similar. To see what I mean, take a look at the code in Listing 1, a JUnit 4 test that has a macro-fixture (a fixture that is called just once before any tests are run), which is denoted by the @BeforeClass attribute:

Listing 1. A simple JUnit 4 test case

package test.com.acme.dona.dep;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertEquals;

import static org.junit.Assert.assertNotNull;

import org.junit.BeforeClass;

import org.junit.Test;

public class DependencyFinderTest {

private static DependencyFinder finder;

@BeforeClass

public static void init() throws Exception {

finder = new DependencyFinder();

}

@Test

public void verifyDependencies() throws Exception {

String targetClss = "test.com.acme.dona.dep.DependencyFind";

Filter[] filtr = new Filter[] {

new RegexPackageFilter("java|junit|org")};

Dependency[] deps =

finder.findDependencies(targetClss, filtr);

assertNotNull("deps was null", deps);

assertEquals("should be 5 large", 5, deps.length);

}

}

JUnit users will immediately note that this class lacks much of the syntactic sugar required by previous versions of JUnit. There isn't a setUp() method, the class doesn't extend TestCase, and it doesn't even have any methods that start with test. This class also makes use of Java 5 features like static imports and, obviously, annotations.

Even more flexibility

In Listing 2, you see the same test, but this time it's implemented using TestNG. There is one subtle difference between this code and the test in Listing 1. Do you see it?

Listing 2. A TestNG test case

package test.com.acme.dona.dep;

import static org.testng.Assert.assertEquals;

import static org.testng.Assert.assertNotNull;

import org.testng.annotations.BeforeClass;

import org.testng.annotations.Configuration;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

public class DependencyFinderTest {

private DependencyFinder finder;

@BeforeClass

private void init() {

this.finder = new DependencyFinder();

}

@Test

public void verifyDependencies() throws Exception {

String targetClss =

"test.com.acme.dona.dep.DependencyFind";

Filter[] filtr = new Filter[] {

new RegexPackageFilter("java|junit|org")};

Dependency[] deps =

finder.findDependencies(targetClss, filtr);

assertNotNull(deps, "deps was null" );

assertEquals(5, deps.length, "should be 5 large");

}

}

Obviously the two listings are pretty similar, but if you look closely, you'll see that the TestNG coding conventions are more flexible than JUnit 4's. In Listing 1, JUnit forced me to declare my @BeforeClass decorated method as static, which consequently required me to also declare my fixture, finder, as static. I also had to declare my init() method as public. Looking at Listing 2, you see a different story because those conventions aren't required. My init() method is neither static nor public.

Flexibility has been one of the strong points of TestNG right from the start, but that's not its only selling point. TestNG also offers some testing features you won't find in JUnit 4.

Dependency testing

One thing the JUnit framework tries to achieve is test isolation. On the downside, this makes it very difficult to specify an order for test-case execution, which is essential to any kind of dependent testing. Developers have used different techniques to get around this, like specifying test cases in alphabetical order or relying heavily on fixtures to properly set things up.

These workarounds are fine for tests that succeed, but for tests that fail, they have an inconvenient consequence: every subsequent dependent test also fails. In some situations, this can lead to large test suites reporting unnecessary failures. For example, imagine a test suite that tests a Web application that requires a login. You might work around JUnit's isolationism by creating a dependent method that sets up the entire test suite with a login to the application. Nice problem solving, but when the login fails, the entire suite fails too -- even if the application's post-login functionality works!

Skipping, not failing

Unlike JUnit, TestNG welcomes test dependencies through the dependsOnMethods attribute of the Test annotation. With this handy feature, you can easily specify dependent methods, such as the login from above, which will execute before a desired method. What's more, if the dependent method fails, then all subsequent tests will be skipped, not marked as failed.

Listing 3. Dependent testing with TestNG

import net.sourceforge.jwebunit.WebTester;

public class AccountHistoryTest {

private WebTester tester;

@BeforeClass

protected void init() throws Exception {

this.tester = new WebTester();

this.tester.getTestContext().

setBaseUrl("http://div.acme.com:8185/ceg/");

}

@Test

public void verifyLogIn() {

this.tester.beginAt("/");

this.tester.setFormElement("username", "admin");

this.tester.setFormElement("password", "admin");

this.tester.submit();

this.tester.assertTextPresent("Logged in as admin");

}

@Test (dependsOnMethods = {"verifyLogIn"})

public void verifyAccountInfo() {

this.tester.clickLinkWithText("History", 0);

this.tester.assertTextPresent("GTG Data Feed");

}

}

In Listing 3, two tests are defined: one for verifying a login and another for verifying account information. Note that the verifyAccountInfo test specifies that it depends on the verifyLogIn() method using the dependsOnMethods = {"verifyLogIn"} clause of the Test annotation.

If you ran this test through TestNG's Eclipse plug-in (for example) and the verifyLogIn test failed, TestNG would simply skip the verifyAccountInfo test, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Skipped tests in TestNG

TestNG's trick of skipping, rather than failing, can really take the pressure off in large test suites. Rather than trying to figure out why 50 percent of the test suite failed, your team can concentrate on why 50 percent of it was skipped! Better yet, TestNG complements its dependency testing setup with a mechanism for rerunning only failed tests.

Fail and rerun

The ability to rerun failed tests is especially handy in large test suites, and it's a feature you'll only find in TestNG. In JUnit 4, if your test suite consists of 1000 tests and 3 of them fail, you'll likely beforced to rerun the entire suite (with fixes). Needless to say, this sort of thing can take hours.

Anytime there is a failure in TestNG, it creates an XML configuration file that delineates the failed tests. Running a TestNG runner with this file causes TestNG to only run the failed tests. So, in the previous example, you would only have to rerun the three failed tests and not the whole suite.

You can actually see this for yourself using the Web testing example from Listing 2. When the verifyLogIn() method failed, TestNG automatically created a testng-failed.xml file. The file serves as an alternate test suite in Listing 4:

Listing 4. Failed test XML file